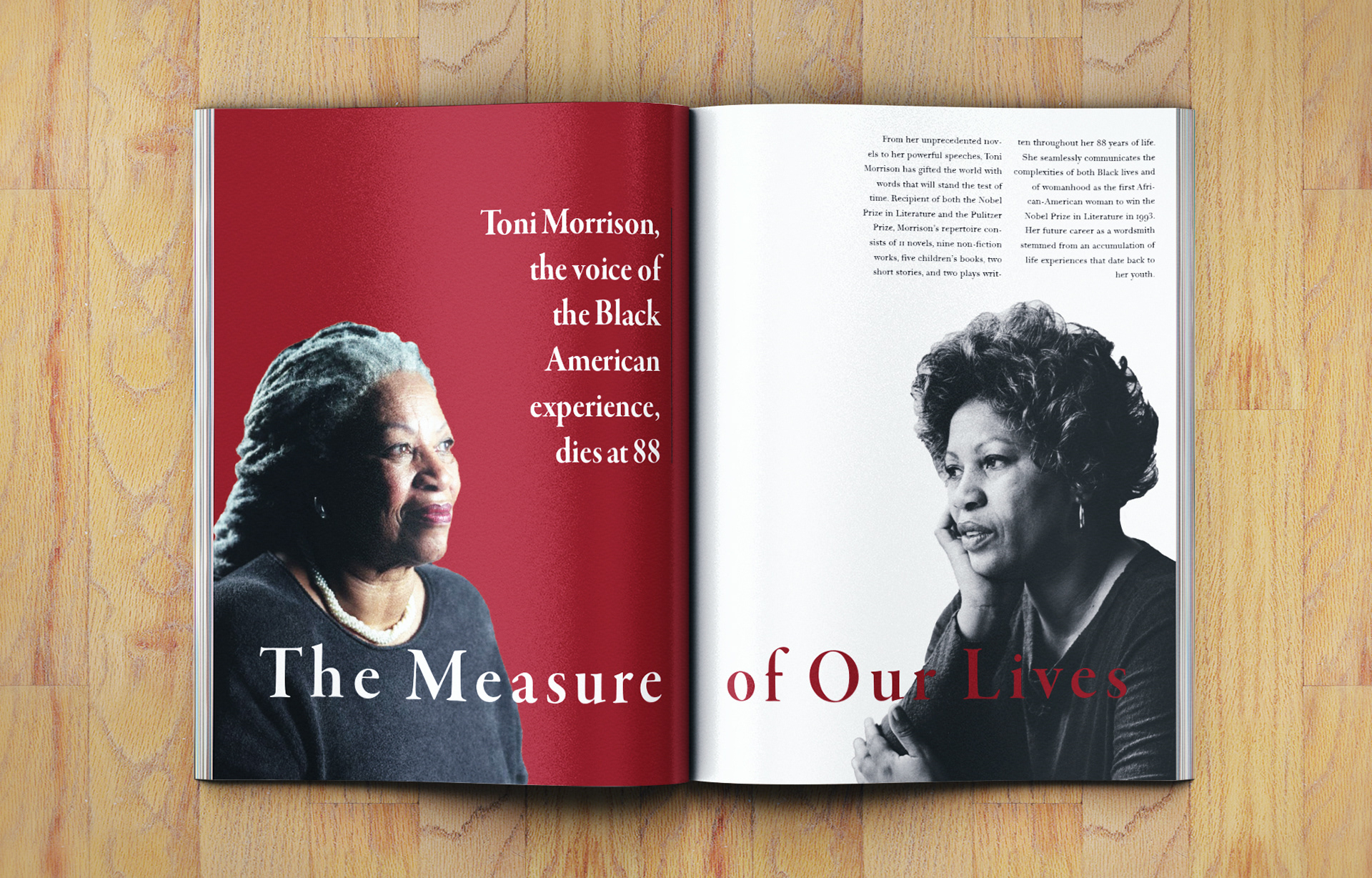

From unprecedented novels to gripping speeches, Toni Morrison gifted the world with words that will stand the test of time. As the first African-American recipient of both the Nobel Prize in Literature and the Pulitzer Prize, she seamlessly communicates the complexities of both Black lives and of womanhood. The Morrison repertoire consists of 11 novels, nine non-fiction works, five children's books, two short stories, and two plays written throughout her 88 years of life. While the majority of her most recognized works were written later in life, Morrison's calling as a wordsmith originates from an accumulation of life experiences that date back to her youth.

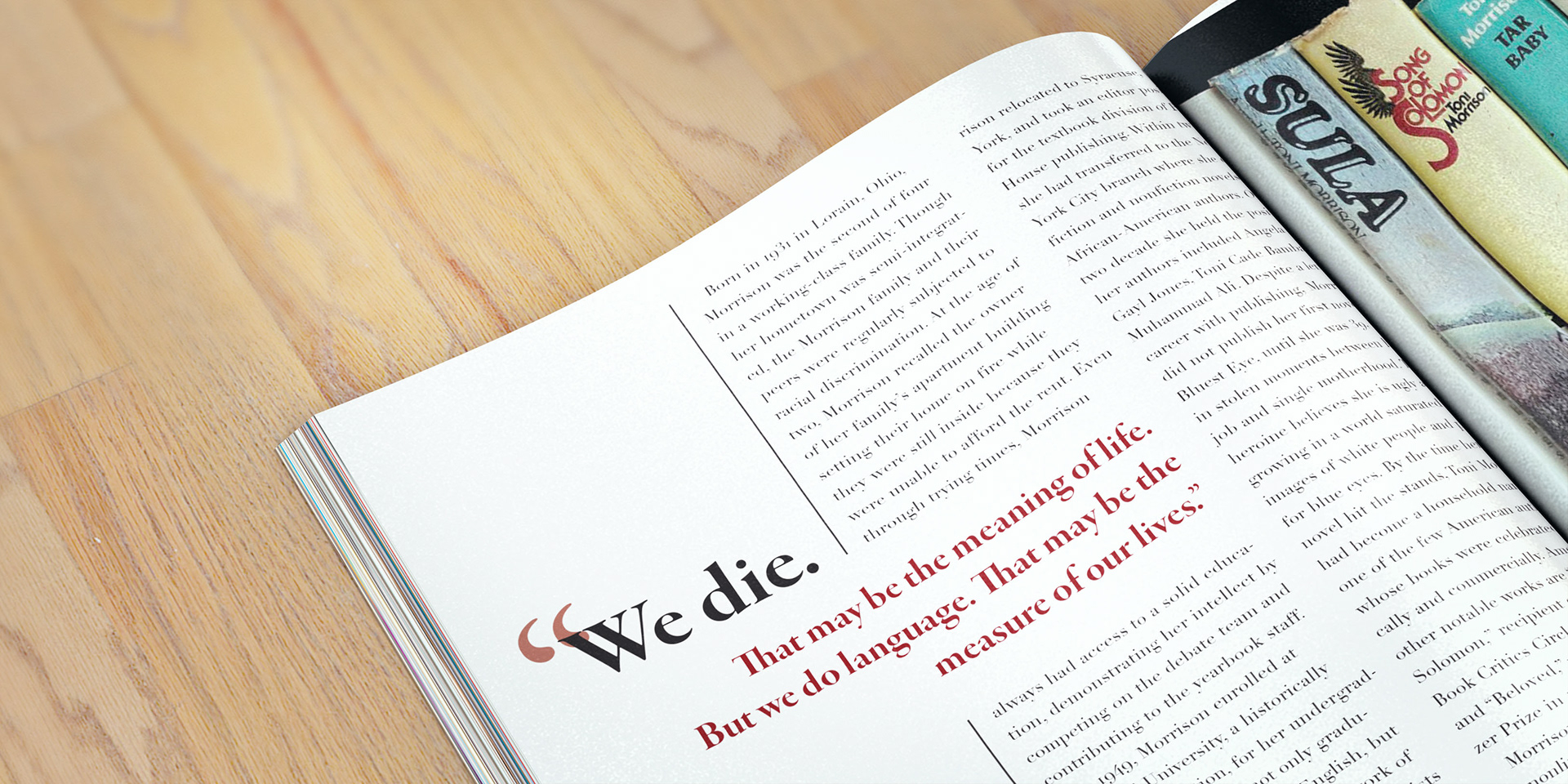

Born in 1931 in Lorain, Ohio, Morrison was the second of four children in a working-class family. Though her hometown was semi-integrated, the Morrison family and their peers were regularly subjected to racial discrimination. At the age of two, Morrison recalls the owner of her family’s apartment building setting their home on fire while they were still inside because they were unable to afford rent. Even through trying times, Morrison expresses gratitude for her continuous access to a solid education, where she demonstrated her intellect by competing on the debate team and contributing to the school yearbook staff.

In 1949, Morrison enrolled at Howard University, a historically Black institution, for her undergraduate studies. She not only graduated with a degree in English, but also with an extensive network of fellow Black writers, artists, and activists that were instrumental to her research and writings. Morrison graduated in 1955 with a Master of Arts in English from Cornell University, yet returned to teach at Howard shortly afterwards. While at the university, she worked alongside the renowned civil rights activist Stokely Carmichael and met her husband, Harold Morrison, with whom she had two children.

After seven years at Howard, Morrison relocated to Syracuse, New York, and took an editor position for the textbook division of Random House publishing. Within two years, she had transferred to the New York City branch where she edited fiction and nonfiction novels by African-American authors. Over the course of the two decades as editor, her authors included Angela Davis, Gayl Jones, Toni Cade Bambara, and Muhammad Ali. Despite a lengthy career with publishing, Morrison did not publish her first novel, The Bluest Eye, until she was 39, writing in stolen moments between her day job and single motherhood. The Bluest Eye's heroine believes she is ugly after maturing in a world saturated with images of white people, leading her to plead with god for blue eyes. By the time her third novel hit the stands, Toni Morrison had become a household name and one of few American authors whose books were celebrated critically and commercially. Among her other notable works are Song of Solomon, recipient of the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1977, and Beloved, winner of the Pulitzer Prize in 1988.

Morrison’s plots were uniquely nonlinear, habitually traversing backwards and forwards in time. This method has the effect of bringing down the exhaustive weight of history on her creations. Her narratives also mingle the voices of men, women, children, and even ghosts in the case of Beloved, delivering multidimensional stories about slavery and its legacy. Beloved was the first of Morrison’s novels to be set during a specific moment in history, rooted in a real 19th-century tragedy nearly a decade after the conclusion of the Civil War. “I look very hard for Black fiction because I want to participate in developing a canon of Black work,” Ms. Morrison said in an interview quoted in The Dictionary of Literary Biography. “We’ve had the first rush of black entertainment, where Blacks were writing for whites, and whites were encouraging this kind of self-flagellation. Now we can get down to the craft of writing, where Black people are talking to Black people.”

Though Morrison is no longer with us, her towering legacy as a voice of the Black American experience remains. “We die,” said Morrison. “That may be the meaning of life. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives.”